Diffusion Models Part I — DDPM = Demolishing + Reconstructing

When it comes to generative models, VAE and GAN are household names. There are also some less mainstream options, such as flow models and VQ-VAE, which have gained popularity — especially VQ-VAE and its variant VQ-GAN, which have recently evolved into “tokenizers for images,” enabling direct use of NLP pretraining methods. Beyond these, there is another previously niche option — Diffusion Models — that is now rapidly rising in the generative modeling field. The two most advanced text-to-image models today — OpenAI’s DALL·E 2 and Google’s Imagen — are both built upon diffusion models.

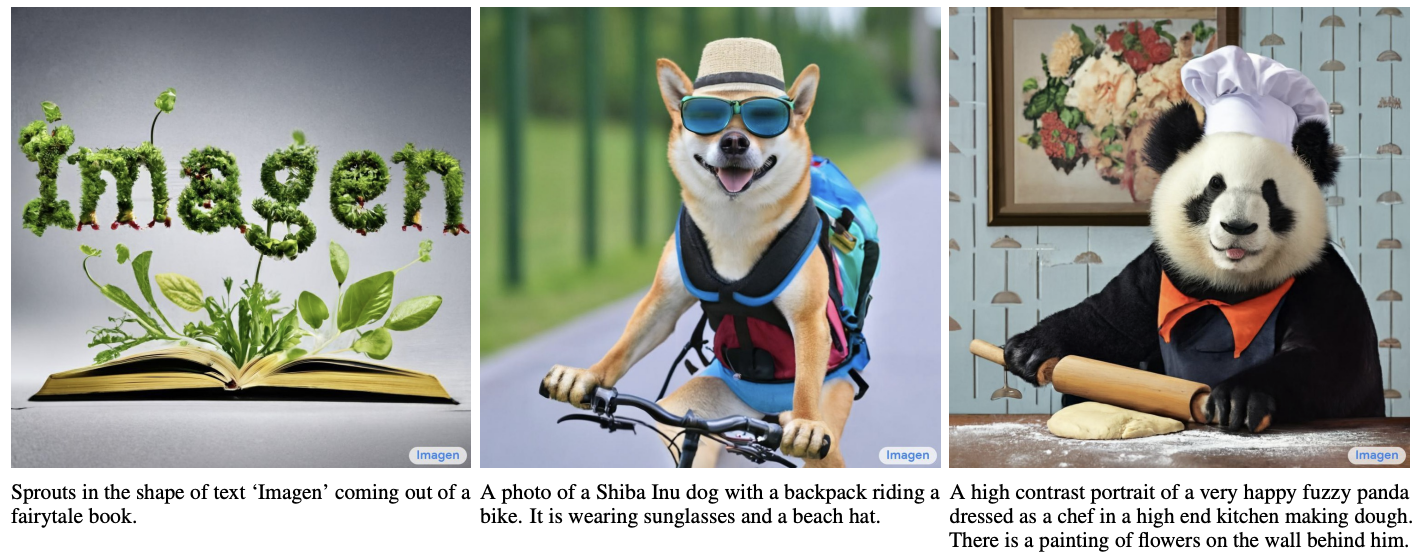

Some examples of text to image by Imagen

It is often said that generative diffusion models are mathematically complex — seemingly much harder to understand than VAE or GAN. Is this really true? Can diffusion models not be explained in plain language? Let’s find out.

A New Starting Point

Typically, diffusion models are associated with concepts like energy-based models, score matching, and Langevin dynamics — essentially, training an energy model via score matching and sampling from it via Langevin dynamics.

Theoretically, this is a mature framework capable of generating and sampling any continuous object (speech, images, etc.). However, in practice, training energy functions is notoriously difficult — especially for high-dimensional data like high-resolution images — and sampling via Langevin dynamics often yields noisy, unreliable results. Thus, traditional diffusion models were mostly confined to low-resolution image experiments.

The recent surge in generative diffusion models began with DDPM (Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Model) in 2020. Although it shares the name “diffusion model,” DDPM is fundamentally different from traditional Langevin-based diffusion models — it represents a completely new starting point.

Strictly speaking, DDPM should be called a “gradual model” — the term diffusion model is misleading. Traditional concepts like energy models, score matching, and Langevin dynamics are largely irrelevant to DDPM and its variants. Interestingly, the mathematical framework of DDPM was already established in the 2015 ICML paper Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics, but DDPM was the first to successfully apply it to high-resolution image generation — sparking the current wave of interest. This shows that a model’s success often depends on timing and opportunity.

Demolishing and Reconstructing

Many articles introduce DDPM by immediately diving into transition distributions and variational inference — a barrage of mathematical notation that scares off many readers (and reveals that DDPM is essentially a VAE, not a diffusion model). Combined with the public’s preconceived notions of traditional diffusion models, this creates the illusion that DDPM requires advanced mathematics. In reality, DDPM can be understood in plain language — it’s no harder than GAN, which has the intuitive analogy of “forgery vs. detection.”

Imagine we want to build a generative model that transforms random noise \(z\) into a data sample \(x\):

\[z \rightarrow x\]We can think of this as “construction”: \(z\) is raw material (bricks, cement), and \(x\) is the finished building. The generative model is the construction crew.

This is hard — hence the decades of research on generative models. But as the saying goes, “destruction is easier than construction.” What if we instead consider demolishing a building step by step? Let $\boldsymbol{x}_0$ be the finished building (data sample), and $\boldsymbol{x}_T$ be the raw materials (random noise). Assume demolition takes $T$ steps:

\[\boldsymbol{x}_0 \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_1 \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_2 \rightarrow \cdots \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_{T-1} \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_T = \boldsymbol{z}\]The difficulty in construction lies in the huge leap from \(\boldsymbol{x}_T\) to \(\boldsymbol{x}_0\). But once we have the intermediate demolition steps \(\boldsymbol{x}_1, \boldsymbol{x}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_T\), we know that \(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_t\) is one demolition step — so the reverse, \(\boldsymbol{x}_t \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}\), is one construction step. If we can learn the transformation \(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\), then starting from \(\boldsymbol{x}_T\), we repeatedly apply:

\[\boldsymbol{x}_{T-1} = \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_T), \quad \boldsymbol{x}_{T-2} = \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_{T-1}), \quad \dots\]Eventually, we reconstruct \(\boldsymbol{x}_0\) — the finished building.

How to Demolish

As the saying goes, “You eat an elephant one bite at a time.” DDPM’s generative process mirrors this “demolish-reconstruct” analogy: it first builds a gradual transformation from data to noise, then learns its inverse to generate data. Hence, DDPM is more accurately called a “gradual model.”

Specifically, DDPM models the demolition process as:

\[\boldsymbol{x}_t = \alpha_t \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t, \quad \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I}) \tag{3}\]where \(\alpha_t, \beta_t > 0\) and \(\alpha_t^2 + \beta_t^2 = 1\). \(\beta_t\) is typically close to \(0\), representing the degree of destruction per step. The noise \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\) can be thought of as “raw material” — each demolition step breaks \(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}\) into “\(\alpha_t \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}\) (remaining structure) + \(\beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\) (new material).”

Repeated application yields:

\[\begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{x}_t &= \alpha_t \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \\ &= \alpha_t (\alpha_{t-1} \boldsymbol{x}_{t-2} + \beta_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_{t-1}) + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \\ &= \cdots \\ &= (\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_1) \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \underbrace{(\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_2) \beta_1 \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_1 + (\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_3) \beta_2 \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_2 + \cdots + \alpha_t \beta_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t}_{\text{Sum of independent Gaussian noises}} \end{aligned} \tag{4}\]Why must \(\alpha_t^2 + \beta_t^2 = 1\)? The bracketed term is a sum of independent Gaussian noises with mean \(0\) and variances \((\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_2)^2 \beta_1^2, (\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_3)^2 \beta_2^2, \dots, \alpha_t^2 \beta_{t-1}^2, \beta_t^2\). By the additive property of Gaussians, the total variance is:

\[(\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_2)^2 \beta_1^2 + (\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_3)^2 \beta_2^2 + \cdots + \alpha_t^2 \beta_{t-1}^2 + \beta_t^2\]Under \(\alpha_t^2 + \beta_t^2 = 1\), the sum of squares of all coefficients in (4) equals \(1\):

\[(\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_1)^2 + (\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_2)^2 \beta_1^2 + \cdots + \beta_t^2 = 1 \tag{5}\]Thus, we can rewrite:

\[\boldsymbol{x}_t = \underbrace{(\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_1)}_{\bar{\alpha}_t} \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \underbrace{\sqrt{1 - (\alpha_t \cdots \alpha_1)^2}}_{\bar{\beta}_t} \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t, \quad \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I}) \tag{6}\]This greatly simplifies computing \(\boldsymbol{x}_t\). DDPM chooses \(\alpha_t\) such that \(\bar{\alpha}_T \approx 0\), meaning after \(T\) steps, the structure is nearly gone — fully converted to noise.

How to Reconstruct

Demolition is \(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_t\), yielding data pairs \((\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{x}_t)\). Reconstruction learns \(\boldsymbol{x}_t \rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}\). Let the model be \(\boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t)\). A natural loss is the Euclidean distance:

\[\left\| \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} - \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) \right\|^2 \tag{7}\]This is close to DDPM’s final form. Rewriting (3) as \(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \frac{1}{\alpha_t} (\boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t)\), we design:

\[\boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) = \frac{1}{\alpha_t} \left( \boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t) \right) \tag{8}\]where \(\theta\) are trainable parameters. Substituting into (7):

\[\left\| \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} - \boldsymbol{\mu}(\boldsymbol{x}_t) \right\|^2 = \frac{\beta_t^2}{\alpha_t^2} \left\| \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t - \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t) \right\|^2 \tag{9}\]Ignoring the weight \(\frac{\beta_t^2}{\alpha_t^2}\), and using (6) and (3) to express \(\boldsymbol{x}_t\):

\[\boldsymbol{x}_t = \alpha_t \boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t = \alpha_t (\bar{\alpha}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_{t-1} \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1}) + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t = \bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \alpha_t \bar{\beta}_{t-1} \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \tag{10}\]The loss becomes:

\[\left\| \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t - \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \alpha_t \bar{\beta}_{t-1} \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t, t) \right\|^2 \tag{11}\]Why not use (6) directly? Because \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\) and \(\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t\) are not independent — given \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\), we cannot sample \(\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_t\) independently.

Reducing Variance

Loss (11) can train DDPM, but it may suffer from high variance, slowing convergence. Why? It requires sampling 4 random variables:

- Sample \(\boldsymbol{x}_0\) from training data.

- Sample \(\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I})\) (two independent samples).

- Sample \(t \in \{1, \dots, T\}\).

More random variables → higher variance in loss estimation.

We can reduce variance by merging \(\bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1}, \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\) into a single Gaussian. By additive property:

\[\alpha_t \bar{\beta}_{t-1} \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} + \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \sim \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, \quad \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I})\]Similarly:

\[\beta_t \bar{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}_{t-1} - \alpha_t \bar{\beta}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t \sim \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\omega}, \quad \boldsymbol{\omega} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I})\]with \(\mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \boldsymbol{\omega}^\top] = \mathbf{0}\) — independent.

Rewriting \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t\):

\[\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_t = \frac{\beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \alpha_t \bar{\beta}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\omega}}{\bar{\beta}_t} \tag{12}\]Substituting into (11):

\[\mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\omega}, \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I})} \left[ \left\| \frac{\beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \alpha_t \bar{\beta}_{t-1} \boldsymbol{\omega}}{\bar{\beta}_t} - \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t) \right\|^2 \right] \tag{13}\]Since the loss is quadratic in \(\boldsymbol{\omega}\), we compute its expectation:

\[\frac{\beta_t^2}{\bar{\beta}_t^2} \mathbb{E}_{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I})} \left[ \left\| \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\beta_t} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t) \right\|^2 \right] + \text{constant} \tag{14}\]Ignoring constants and weights, DDPM’s final loss is:

\[\left\| \boldsymbol{\varepsilon} - \frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\beta_t} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t) \right\|^2 \tag{15}\]Note: In the original paper, \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta\) corresponds to \(\frac{\bar{\beta}_t}{\beta_t} \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta\) here — results are identical.

Recursive Generation

After training, we generate from \(\boldsymbol{x}_T \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I})\) by iterating (8) \(T\) times:

\[\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \frac{1}{\alpha_t} \left( \boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t) \right) \tag{16}\]This is like greedy search in autoregressive decoding. For random sampling, add noise:

\[\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1} = \frac{1}{\alpha_t} \left( \boldsymbol{x}_t - \beta_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\boldsymbol{x}_t, t) \right) + \sigma_t \boldsymbol{z}, \quad \boldsymbol{z} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \boldsymbol{I}) \tag{17}\]Typically, \(\sigma_t = \beta_t\) — matching forward and reverse variances. Unlike Langevin sampling (which iterates infinitely from any point), DDPM starts from noise and iterates \(T\) steps — fundamentally different.

This resembles Seq2Seq decoding — autoregressive and slow. DDPM uses \(T=1000\), meaning 1000 model evaluations per image. This is a major drawback — many works aim to speed it up.

Comparing to PixelRNN/PixelCNN: both are autoregressive, but PixelRNN/PixelCNN generate pixel-by-pixel, requiring a fixed order (inductive bias). DDPM treats all pixels equally — no bias. Also, DDPM’s \(T\) is fixed (e.g., 1000), while PixelRNN/PixelCNN’s steps scale with image resolution (\(\text{width} \times \text{height} \times \text{channels}\)) — DDPM is faster for high-res images.

Hyperparameter Settings

In DDPM, \(T=1000\) — larger than many expect. Why? For \(\alpha_t\), the original paper’s setting (translated to our notation) is:

\[\alpha_t = \sqrt{1 - \frac{0.02t}{T}} \tag{18}\]Why monotonic decrease? Both relate to data context. We used Euclidean distance (7) for reconstruction — poor for images (causes blur in VAE). Larger \(T\) ensures \(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{x}_t\) are closer, reducing blur.

For \(\alpha_t\): when \(t\) is small, \(\boldsymbol{x}_t\) is image-like — use large \(\alpha_t\) to keep \(\boldsymbol{x}_{t-1}\) and \(\boldsymbol{x}_t\) close. When \(t\) is large, \(\boldsymbol{x}_t\) is noise — use smaller \(\alpha_t\). Can we use large \(\alpha_t\) throughout? Yes, but \(T\) must be larger. From (6), we need \(\bar{\alpha}_T \approx 0\). Estimating:

\[\log \bar{\alpha}_T = \sum_{t=1}^T \log \alpha_t = \frac{1}{2} \sum_{t=1}^T \log \left(1 - \frac{0.02t}{T}\right) < \frac{1}{2} \sum_{t=1}^T \left(-\frac{0.02t}{T}\right) = -0.005(T+1) \tag{19}\]For \(T=1000\), \(\bar{\alpha}_T \approx e^{-5}\) — close enough to 0. Using large \(\alpha_t\) throughout requires larger \(T\).

Finally, in \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_\theta(\bar{\alpha}_t \boldsymbol{x}_0 + \bar{\beta}_t \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, t)\), \(t\) is explicitly input because different \(t\) handle different “levels.” Ideally, we’d have \(T\) separate models — instead, we share parameters and condition on \(t\). As per the paper’s appendix, \(t\) is encoded via sinusoidal positional encoding (as in “Transformer Upgrade: 1. Sinusoidal Positional Encoding”) and added to residual blocks.

Summary

This article introduced DDPM — the latest generative diffusion model — via the “demolish-reconstruct” analogy. With plain language and minimal math, we derived the same results as the original paper. DDPM can be as intuitive as GAN — it avoids VAE’s “variational” and GAN’s “divergence/transport” — arguably simpler than both.

References:

https://kexue.fm/archives/9119

If you found this useful, please cite this as:

Li, Ruiyu (Jan 2026). Diffusion Models Part I — DDPM = Demolishing + Reconstructing. https://ruiyli.github.io.

or as a BibTeX entry:

@article{li2026diffusion-models-part-i-ddpm-demolishing-reconstructing,

title = {Diffusion Models Part I — DDPM = Demolishing + Reconstructing},

author = {Li, Ruiyu},

year = {2026},

month = {Jan},

url = {https://ruiyli.github.io/blog/2026/Diffusion-Models-Part-I/}

}

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: